What’s in a Frame: The Temporal Framing of Climate Change in the Netherlands and Ireland

Written by Tuin T. O. Scheffer

Tuin is currently doing the Research Master’s in Modern History & International Relations at the RUG. She specialises in European Union affairs and policy formation. This essay was submitted in January 2025 as part of the course on Theory of Modern History and IR.

What’s in a Frame: The Temporal Framing of Climate Change in the Netherlands and Ireland

Introduction

Climate change, or more specifically anthropogenic climate change, refers to the long-term changes in weather patterns observed over the last several decades resulting from human action (Pahl et al., 2014).

The crisis this constitutes is an escalating threat to modernity and its accompanying way of life (Hardy, 2003). From global warming to extreme weather events, environmental degradation, and the pressing finite nature of many of the resources needed to sustain the modern world, it is becoming increasingly clear that action is necessary (Whitmarsh, 2011; Pahl et al., 2014, p. 375; Hilson, 2018; Folkers, 2021).

Time and its politics are crucial to understanding climate change and gathering support for policy in the field (Herberz et al., 2023). There are several temporal dimensions that characterise the biophysical sphere in which climate change exists. The most important of these are its extension into the future, and the temporal distance (or time lag) between cause and effect (Prozorov, 2010; Pahl et al., 2014, p. 376).

Beyond the biophysical temporality, responses to climate change are also limited by human temporality, such as the time of politics and the politics of time (Kang et al., 2023).

The increasing pressure the climate crisis puts on modernity (Folkers, 2021) therefore presents a significant political challenge. And its temporal dimension means that at its core, any response to climate change is inherently a political negotiation of time beyond mere future predictions or historical responsibilities. Instead this process is about how different actors frame and utilise temporal perspectives (Pahl et al., 2014).

This paper therefore argues that temporal framing is a critical expression of the politics of time and significantly shapes national climate policies (De Boer et al., 2010).

The European Union (EU) has positioned itself as a global leader in climate action, vowing under European Climate Law to become climate-neutral by 2050 (Manners, 2002; De Roeck et al., 2017; EC, n.d.). However, the EU and its Member States (MS) share competence in combating climate change (EC, n.d.). Therefore a multitude of national contexts and frames exist in the MS, resulting in nationally different performances in combatting climate change (Daviter, 2007).

“Framing” refers to the process by which actors highlight aspects of issues’ perceived reality, to the detriment of others. This significant process can influence how problems are understood and how they are acted upon (De Boer et al., 2010; Pahl et al., 2014, p. 376; Stanley et al., 2021). This in turn affects the effectiveness of European-wide climate action. To achieve the European goal of climate neutrality, it is paramount to understand variations in the Member States’ temporal framing of the climate crisis (Dirikx & Gelders, 2010).

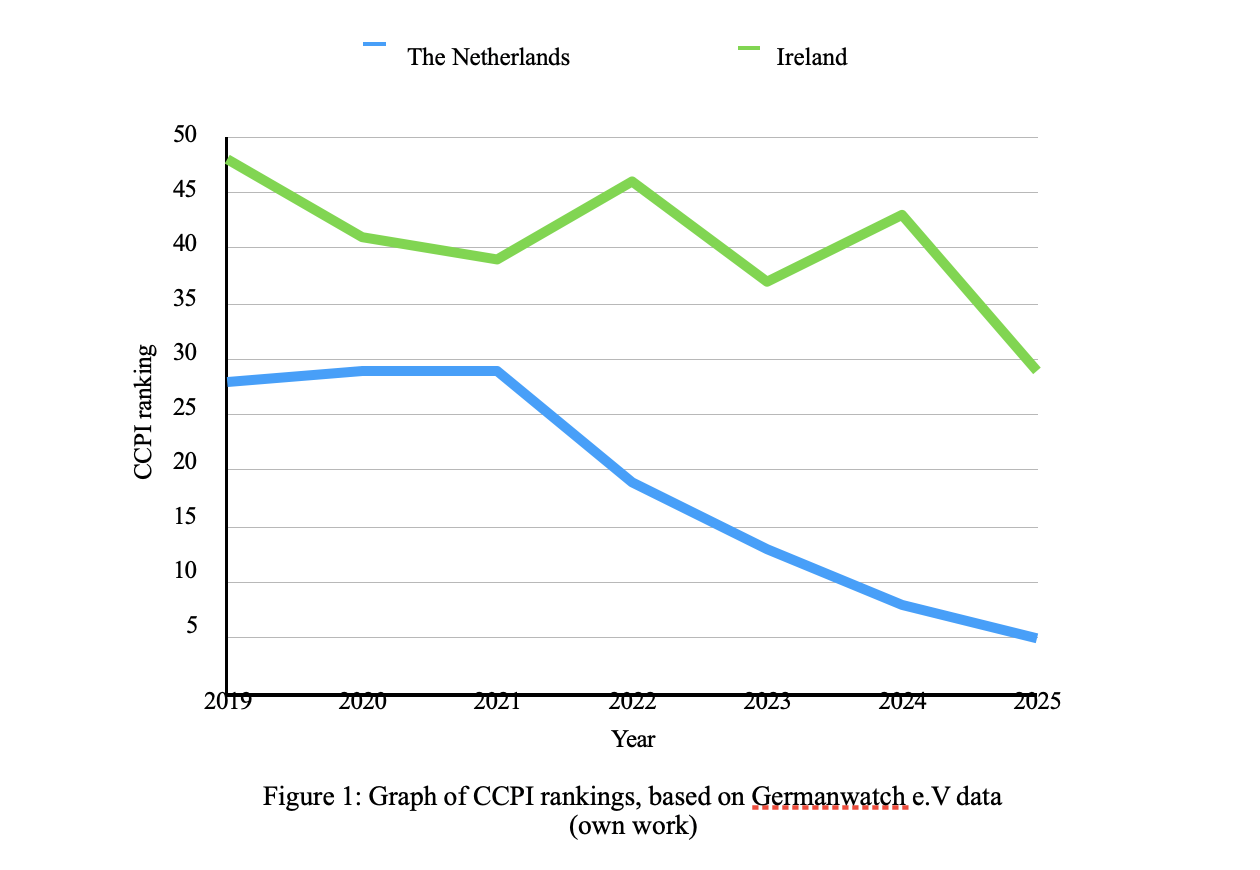

In this regard, it is especially interesting to investigate the framing of two countries that have historically been on opposite ends of European environmental performance (Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025). Additionally, these two countries have distinct historical relationships with their environment and the creation of policy in this field (Coghlan, 2007; Hoeksema, 2007; Kennedy, 2011; Pettenger, 2016; Torney, 2017), that may lead to distinct approaches to climate temporalities.

That is why I propose to address the research question: “How did Ireland and the Netherlands temporally frame the climate crisis in comparison after the Paris Agreement?”.

The relevance of this research is two-fold. Academically, the research contributes to the ongoing investigation of temporal climate frames and the interplay between different types of framing on a European level. While framing theory is widely used in political and social science research, studies on climate change often overlook the inherent dimension of temporality. This research question addresses this gap by focusing on the temporal aspects of climate framing (Hilson, 2018; Herberz et al., 2023). Furthermore, it highlights the significance of the politics of time by delving into how time is “politicised” in climate discourse. The research thus investigates how the two cases construct urgency, responsibility, and the perceived distance of climate impacts, as well as furthers the understanding of policy reception (Garrard, 2019). Socially, the research is also relevant, as it sheds light on the subtle yet powerful impact of communication on public perception and engagement with climate policy. This ultimately supports both national and European abilities to respond effectively to climate change one of the most pressing challenges of our time (De Boer et al., 2010; Ansari et al., 2013, p. 1034; Pahl et al., 2014, p. 376; Stanley et al., 2021; Kang et al., 2023)

This research paper details a comparative case study of Ireland and the Netherlands. It analyses the governments’ temporal framing of the climate crisis in governmental decrees from 2018 and 2019, respectively. By investigating how the two countries temporally framed the climate crisis, this research addresses how temporal narratives influence national climate action.

Consequently, it offers insight into the complex interplay between time, politics, and environmental governance.

I first review the existing literature on the temporal framing of climate change and its influence on governmental action and national environmentalism. Following this, the theoretical framework will expand on the concepts and theories used in the research, as well as their purpose. The methodology will then expand on the employed method of analysis and the analysed data, as well as defend the choices made for the research in this essay. Then the findings of both the Netherlands and Ireland are discussed. First separately, and then in a comparative context, that highlights similarities and differences, and reflecting on the potential implications of those. Finally, I will summarise and interpret the main findings, attempt to answer the research question, and suggest avenues for future research. In the conclusion, it is found that the Netherlands and Ireland frame the effects of climate crisis differently. However, both countries create a present urgency for action.

1. Literature Review

This literature review addresses how the Anthropocene, temporality, framing theory, and the climate policies of Ireland and the Netherlands are represented in the literature. This situates the research in the wider debates on the politics of time and climate change.

1.1. What is the Anthropocene?

The beginning of this century was marked with the coining of the term “Anthropocene”. The concept began to do the rounds in academic spheres as scholars increasingly took note of the magnitude of human impacts on the Earth systems (Malhi, 2017, p. 25.3). While many of the ideas embedded in the concept were not new, the timing of its promotion and its ambitious framing of many ideas into a single word boosted is usage and popularity.

Essentially, the Anthropocene posits that the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have been materially different from earlier ages due to the growing influence of human thought and action on the shaping of both its future and its planetary environment (Ruddiman, 2013; Lewis & Maslin, 2015; Malhi, 2017, p. 25.3-25.4)

It must be noted, however, that the Anthropocene as a concept does not (yet) refer to a new geological epoch, despite multiple geological organisations recommending that it would be included in the geological timeline. Many geologists still oppose the idea and argue that a lot more time and scientific evidence would be needed to cement it as such (Malhi, 2017, p. 25.5). Additionally, even within the field of social sciences, the concept is still much-debated (Ruddiman, 2013; Lewis & Maslin, 2015, p. 177). Still, as epochs indicate the most significant forms of life and their influence on environments, there is a strong case for the Anthropocene as an age of its own (Malhi, 2017, p. 25.6).

Especially as scholars argue that the environmental impact of today’s policies will continue into the distant future (Chakrabarty, 2020; Winter, 2020, p. 279; Folkers, 2021). Consequently, claims are laid on the ecosystems, resources, and climate of today and to which humanity is entitled (UN, 2022). This means that future generations are being harmed in their right to a liveable environment (Winter, 2020). Therefore, the principle of Intergenerational Environmental Justice (IEJ) is under significant strain and also more important than before. However, authors such as Hiskes (2021) and Gosseries (2008), in their investigation of legal multi-generationalism, citizenship, and the possibilities of future generations’ rights, have also identified issues with advocating for the rights of nonexistent people. This further highlights the importance of continued research on climate change and how it both impacts and is impacted by our understanding of time.

1.2. Temporality in the Literature

While the study of time has long since involved the study of climate change, the emergence of the Anthropocene has sparked an increased research interest in the role of time in environmentalist academic work (Hilson, 2018, p. 364; Edensor et al., 2019).

Generally, research on how climate change is framed does not concern temporality. Instead, the focus is on what to call the issue, how to combat it, and what actors are involved (Daviter, 2007; Pahl et al., 2014; Herberz et al., 2023). However, systems of justice and social regulation are fundamentally the expression of how temporal and spatial relationships are connected. Temporality is thus linked to climate change in three ways; the risk in future, the effects in the present, and the responsibilities in the past (Hilson, 2018). Therefore a conceptualisation of climate change has to include a consideration of its temporality, to make its dangerous consequences move from the far-off future to the same, yet far nearer, next-generation future (Pahl et al., 2014; Hilson, 2018).

However, the perception and discussion of time in relation to climate change is complex and oftentimes paradoxical. This is largely because two contrasting feelings exist side by side: it is never too soon to act, yet it is also too late for action. This discourse simultaneously emphasises the urgency and need for immediate change, but also the certainty of irreversible damage that makes any action damage control (Garrard, 2019). This duplicity can largely be attributed to what Nixon (2011) describes as “slow violence”, which refers to the almost imperceptible nature of climate change that in turn makes it difficult to appoint it as a crisis (Garrard, 2019).

The temporal therefore cannot be easily separated from the spatial (Prozorov, 2010; Hilson, 2018, p. 364), and thus temporal frames have the potential to cause significant disruption to legal, political, and social proceedings (Hilson, 2018). However, existing socio-legal literature on climate change has largely considered issues of scale and place, without directly involving time as a separate element (Pahl et al., 201). This demands an investigation of how temporal frames are applied in the literature on climate change when it is applied.

1.3. Application of Framing Theory

Framing theory is a widely adopted method in research on governance. Policy framing research addresses the role of political issue definitions in the policy-making process (Daviter, 2007). It studies the process by which issues, decisions, and events obtain meaning from different perspectives. It highlights certain aspects of a situation at the expense of others. This process has been shown to affect people’s decision preferences, especially under uncertain conditions (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 104; Hänggli & Kriesi, 2012; Dewulf, 2013). Framing therefore not only relates to action but is an action in itself (Dewulf, 2013, p. 322).

Policies of adaptation regarding climate change require a series of decisions (De Boer et al., 2010), that can be divided into three key phases. Firstly, understanding, in which a problem is detected, defined, and framed as information on the issue is gathered. Secondly, planning, in which options of action are developed, assessed and selected, based on the frame or interpretation of the issue. Finally, the problem is managed, meaning that the frame-guided action is implemented, monitored, and evaluated based on the actors’ values and frames guiding the initial problem. Therefore, framing is a crucial process in every part of this process (De Boer et al., 2010; Dewulf, 2013, p. 322-323).

Garrard (2019) draws attention to the importance of the historical and cultural contexts of time. He discusses how different understandings of time and temporality influence how climate change is framed and therefore understood. He finds this specifically important, as temporal frames shape our ethical responsibilities and political responses. Temporal framing thus has a significant impact on ethics and politics (Garrard, 2019; Stanley et al., 2021).

Brace and Geoghegan (2010) agree by stressing that it is crucial to examine the human experience of climate change in the analysis of the crisis. Similar to Edensor et al. (2019), they argue that the Anthropocene and climate change demand a more complex engagement with temporality instead of relying on simple linear projections and predictions of future impacts and historical trends. Within the existing debates and literature, there is thus a strong call for a more diverse and humane approach to climate change and its temporalities.

The literature thus also finds that frames are subject to change and evolution as society and its priorities evolve around them (Brace & Geoghegan, 2010; Vink et al., 2012; Malhi, 2017; Torney, 2017; Edensor et al., 2019). As will be further discussed in the next subsection, this impacts conducted research. In the context of this paper’s research, this raises the question; how have Ireland and the Netherlands framed the temporality of climate change in general?

1.4. Dutch and Irish Climate Change Policy

Distinct national approaches to climate change policy can be understood through the lens of framing, that shapes definitions and approaches within the broader context of the EU (Daviter, 2007).

The Netherlands, as a low-lying country, has a history characterised by fighting water (Hoeksema, 2007). The country is also often praised as a frontrunner in adaptation policy (Kruitwagen et al., 2009; Mees & Surian, 2023). However, this praise should be negated a bit, as the Netherlands is also one of the nations most vulnerable to climate change in the West and therefore has a strong incentive to reduce emissions and combat climate change (Pettenger, 2016; Mees & Surian, 2023).

In researching Dutch climate policy, a clear frame and frame evolution became evident. Most of the literature up until around the 2010s focused on the Dutch fight against water. This is understandable, given the Netherlands’ vulnerability to rising sea-levels (Ansari et al., 2013; Pettenger, 2016; Mees & Surian, 2023). However, there are other factors to Dutch climate policy. The country is after all, next to being vulnerable, also an extreme European polluter. This has to be seen in the context of the Netherlands’ dense population, but the country also houses several very polluting industries, such as a large dairy, meat, and horticulture industry (Van Grinsven et al., 2019; Lamkowsky et al., 2024). In recent years the country has even faced a lot of controversy within the EU for consistently failing to meet emission reduction targets, and opposing more ambitious European goals in the Councils and Parliament (Van Grinsven et al., 2019; Lamkowsky et al., 2024).

Still, the Netherlands ranks among the EU MS with the highest eco-efficiency (Van Grinsven et al., 2019). The reviewed literature mainly contributes to the Netherlands’ long history of working with and against water. Pettenger (2016) argues that this has created a deeply ingrained national narrative of being master over nature, which in turn translates to a proactive approach to combatting climate change. Especially sea-level rise and flood risk are noted as being a major temporal concern for the Netherlands (Vink et al., 2012; Pettenger, 2016, Mees & Surian, 2023). In the literature, Dutch climate policy often has a long-term temporal framing, as articles often refer to the predicted sea-level rise in 2100 (Vink et al., 2012). However, in some instances, there are also references to medium-term temporal framing, such as the European ambition to be climate-neutral in 2050 (Mees & Surian, 2023).

Ireland, on the other hand, ranks among the bottom of EU MS in terms of eco-efficiency (Van Grinsven et al., 2019). This might very well be because Ireland has a very different history and relationship with its environment, and therefore frames the temporality of climate change differently. Torney (2017) and Coghlan (2007) highlight the difficulty Ireland has faced in enacting climate legislation. They note that Irish policy in this field is characterised by delay and protraction because much time elapses between the recognition of the problem and the creation of legislation.

Coghlan (2007) ascribes this to weak domestic consensus, which reveals a lack of future orientation. In the articles, there are no references to any long-term framing of climate change (Coghlan, 2007; Kennedy, 2011; Ansari et al., 2013; Torney, 2017), which, as stated, was present in the literature on Dutch policy. The literature also often focuses on international climate targets and obligations (medium-term frame), as well as Ireland’s inability to consistently meet them. This indicates a gap between short-to-medium-term political commitments and actual emission reductions over time, that Coghlan (2007) attributes to the short-term economic priorities Ireland held during that time, compared to the long-term climate goals posed by the international community. The authors also noted that because Irish climate policy has mainly been driven by European policy, it has been very little uniquely efficient or innovative (Kennedy, 2011).

However, in recent years Ireland has greatly improved its CCPI ranking (Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025). Irish temporal goal orientation might therefore have changed around 2018 (See Figure 1).

2. Conceptual framework

This part of the paper defines the concepts of importance and operationalises them as variables for the analysis. Additionally, it explains framing-theory as the theoretical basis for the research and the employed frames, as adapted from De Boer et al. (2010).

2.1. Concepts

The main concepts used in this research are temporality and climate change. As stated in the Literature Review, while the study of time has for a long time involved the study of climate change, the latter has only recently started incorporating the concept of temporality (Hilson, 2018, p. 364). Yet for as long as people have existed, they have attempted to imagine and predict what is to come and understand what has happened. Additionally, the climate is much older, and for as long as there has been a natural climate, it has also been subject to change. Fluctuations in temperatures, sea levels, and ecosystems are normal (Moser, 2010; Kittel, 2014). However, humanity’s actions and future orientation obtained such an effect on the world and its environment, which, as was established earlier, accumulated into the emergence of the Anthropocene (Ruddiman, 2013; Lewis & Maslin, 2015; Hilson, 2018; Folkers, 2021, p. 10). And with the Anthropocene, academic interest in the relationship between temporality and climate change, also increased (Pahl et al., 2014; Edensor et al., 2019). Hiskes (2009, 2021), Chakrabarty (2020), and Kittel (2014) therefore introduce the idea that climate change is forcing us to come to terms with a reevaluation of our position in time and the effects of our actions across generations. In the following sections, I shall explain what is understood with the main concepts for this research paper.

2.1.1. Climate change

The first concept of importance to this research is climate change. More specifically anthropogenic climate change. As the aim of the research is to investigate how Ireland and the Netherlands frame the temporality of climate change, this concept is used to guide the research.

Anthropogenic climate change refers to the environmental change that is a direct result of human consumption and production since the Industrialisation (Moser, 2010; Kittel, 2014).

Climate change causes stress on environments through rising temperatures and sea levels, and increasing frequencies of extreme weather events. This causes what is known as the triple planetary crisis (loss of biodiversity and ecosystems, and pollution) (Mortreux & Barnett, 2008, p. 105; Kittel, 2014; Hiskes, 2021; Crookes et al., 2022; p. 437). Furthermore, such changes are associated with significant economic and social impacts (Crookes et al., 2022).

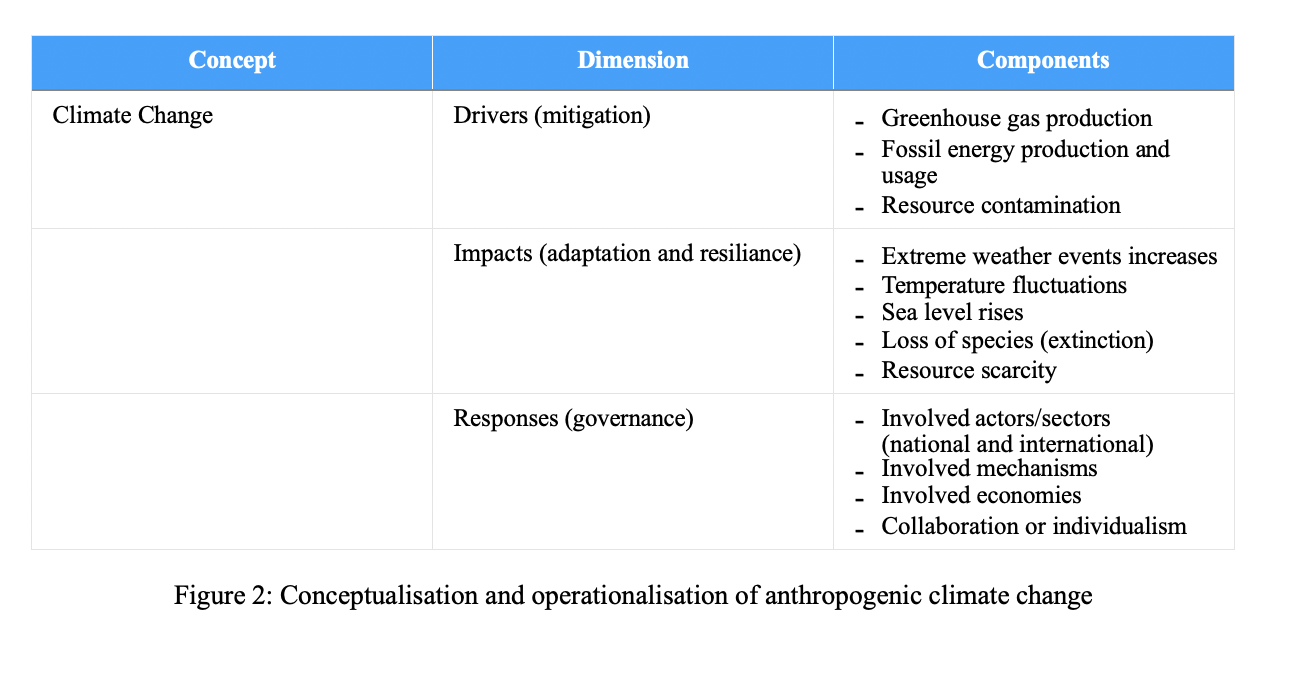

The research conducted for this paper focuses on the framing of climate change and its temporality in the two case-study countries. Within the adaptation of De Boer et al.’s (2010) framework, anthropogenic climate change therefore denotes the goal orientation, and so its framing aims either for the promotion of positive outcomes or the prevention of negative outcomes. For the effective progression of the research, it is necessary to move the conceptualisation away from the abstract challenge posed by “climate change” to the concrete and measurable dimensions. Within policy, a concept can be broken down into cause, effect, and solution (Hardy, 2003). It therefore makes sense to have the conceptualisation of the investigated issue in this research match its conceptualisation in the policy documents. Therefore, the research investigates how the “drivers”, “impacts”, and “responses” of and to climate change are framed by the Netherlands and Ireland (Hardy, 2003).

Drivers are the components that fuel climate change, such as the production of greenhouse gasses, the contamination of resources, and the production and usage of fossil fuels. Its frame is dependent on the question of mitigation. Impacts refer to the results of climate change, of which the case studies need to address how they will adapt and make the countries resilient to for example sea level rises and increases in extreme weather events. Finally, responses refer to the actions to be taken against climate change. Figure 2 summarises these dimensions and components of anthropogenic climate change that will be used for the analysis in this research paper.

2.1.2. Temporality

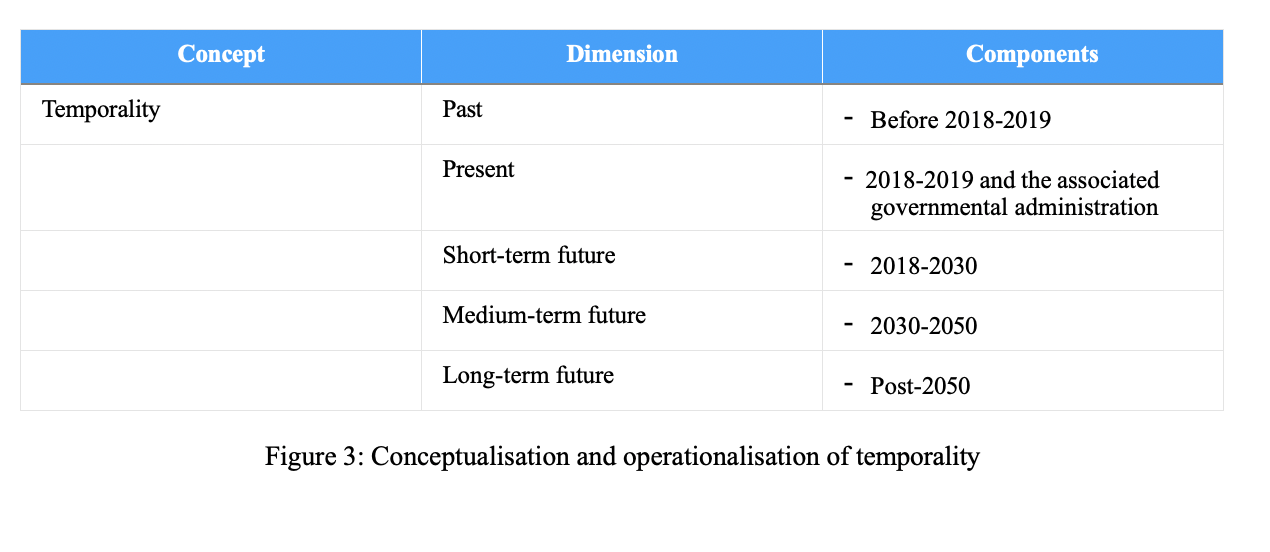

With temporality, this paper refers to how time is politicised in the frames of the two analysed countries. This conceptualisation is based on the perceptual distance in the frame-based approach to situated decision-making on climate change as described in De Boer et al. (2010).

This political usage of time can distance as well as draw events and developments closer, thereby either promoting or discouraging familiarity or urgency (Pahl et al., 2014).

The temporal distance in which climate change and its consequences are framed thus for a large part dictates the urgency people understand action to have (Pahl et al., 2014; Herberz et al., 2023). For example, Hilson (2019) finds that there are largely three ways of temporally framing climate change; in the future, the present, and the past. This politicised usage of time dictates what is important. A future frame, for example, places a risk in the future, and depending on how far away that future is, the less urgent it is to take action. A historical frame, on the other hand, focuses attention on historical responsibilities and the question of who is liable for current consequences (Garrard, 2019).

In this research, Hilson’s three-way temporal frames are expanded upon. Here, the temporality of climate change is framed in five different ways. Firstly there are references to the past, which constitutes all references to climate change and responses before the reviewed climate agreements. Secondly, there are references to the present, that entails the time of the adopted climate agreements and associated governmental administrations (Rutte III in the Netherlands, and the Dáil Éireann under Leo Varadkar in Ireland). Finally, there are references to the short-, medium-, and long-term futures, that respectively refer to the time until the first climate goal, the time between the first and second climate goals, and the time after the second climate goal.

Figure 3, like Figure 2, summarises these dimensions and components of the concept to be used in the analysis.

2.2. Theory

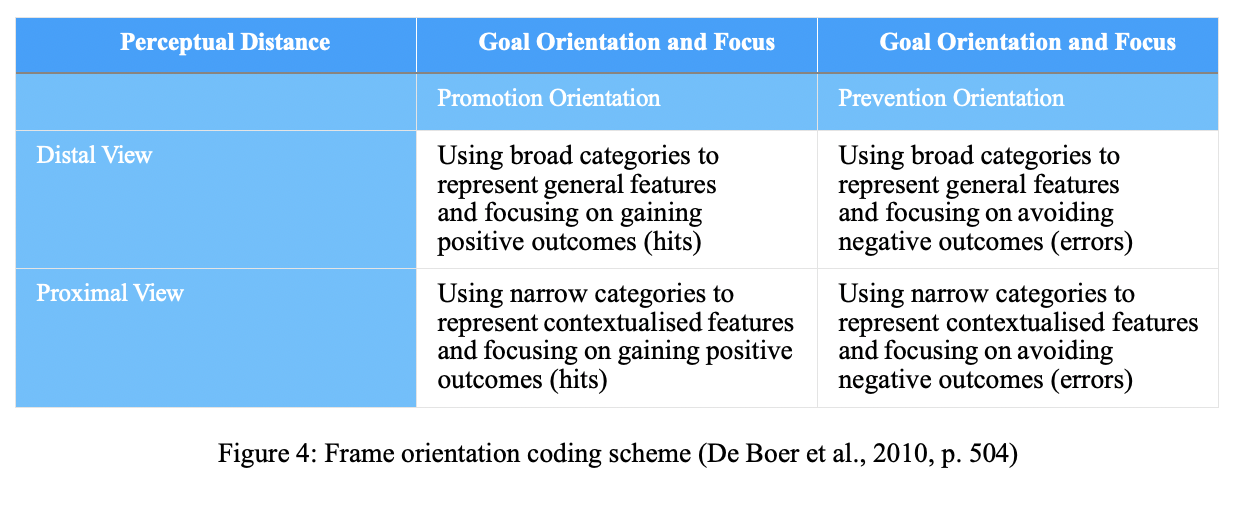

As mentioned, this research paper makes use of framing theory and employs the framework orientation presented by De Boer et al. (2010, p. 504) for this specific purpose (see Figure 4).

Additionally, the Literature Review already analysed what is understood with framing in the existing body of academic work. What is thus primarily important to expand upon in this subsection, is how framing theory works and is applied within the research.

Several studies examined the effectiveness of different kinds of frames on different topics, without that conclusions were drawn about the elements common to persuasive frames. There is thus a large inventory of specific results on the persuasiveness of alternative frames on different issues, but a general theory that allows the anticipation of which frames are likely to emerge as most applicable on an issue remains missing (Chong & Druckman, 2007).

Despite this lack of coherent expectations on a frame’s persuasiveness, framing theory finds that the way information is presented (the “frame”) influences how people perceive and understand that information. Within the processes of policy creation, the success of the policy depends on the initial perception of proposals (Dewulf, 2013, p. 322-323; Torney, 2017; Mees & Surian, 2023, p. 08). The purposeful highlighting or negating of certain aspects of an issue supports certain approaches to an issue (Hänggli & Kriesi, 2012).

In this research, framing theory is used to stipulate a model of policy creation where an orientation or focus of a policy communication motivates the perception of the addressed issue, leading to the degree of success of said policy. This model forms the foundation of the research question and the methodology used to address it, on which the following chapter goes into further detail.

3. Methodology

This section sets out the research design by illustrating framing theory and expanding on the methods of data collection and analysis. To answer the research question, I will conduct a frame analysis.

3.1. Design

The research this paper reports on consists of a case study that performs a frame analysis on Dutch and Irish governmental publications from 2018-2019 and their stance on and approach to climate change. As mentioned in previous chapters, frames are used to understand the world and its issues through the highlighting and downplaying of certain aspects of reality, which in turn influence interpretations and guide decision-making (De Boer et al., 2010; Hänggli and Kriesi, 2012; Dewulf, 2013; Herberz et al., 2023).

Framing therefore has a large influence on both the academic and social understanding of complex issues such as climate change, and investigating how nations frame the topic, can help with the creation of the most effective policy in combatting climate change (Dewulf, 2013; Herberz et al., 2023).

Chong and Druckman (2007, p. 106-108) set out the steps for performing a frame analysis. Firstly, the researcher needs to identify an issue or event within a set time, as a frame in communication can only be defined in relation to an event or issue at a specific point in time. Secondly, the goal of the research needs to be isolated, as this informs the specific frame the research focuses on. Thirdly, the initial set of frames for the issue is put into a coding scheme after their identification. The coding scheme can be based on the prior academic and popular literature, as these provide the “culturally available frames” emphasising common themes (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 107). These frames then also need to be coded, to clarify how a particular frame can be identified in the literature. Fourthly, after the identification of the investigated frames, the next step is the selection of sources for content analysis. Finally, this sample is analysed by identifying the presence or absence of the defined frames.

As established earlier in this essay, the analysis is focused on the framing of climate change’s temporality around 2018-2019. This was an interesting time as governments worked to implement the Paris Agreement into their legislation and the European Union worked to establish the European Green Deal. Therefore both the Netherlands and Ireland came out with a national climate adaptation framework during this period (AZ, 2022; gov.ie, 2025). Analysing the specific effects of the Dutch and Irish frames is beyond the scope of the current research. This goal may set up future research on the effects of temporal framing. Especially given the change in the CCPI performance of both countries (Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025) (see Figure 1), it would be interesting to see if differences in temporal climate framing contribute to the degree of success of national climate policy. The analysed frames are based on the coding scheme presented by De Boer et al. (2010, p. 504). As expanded upon in the Conceptual Framework, the Goal Orientation in this frame represents climate change adaption policies as presented in the Irish NAF and Dutch Klimaatakkoord. The Perceptual Distance refers to the temporality with which climate change and adaptation policies are regarded. Additionally, these frame orientations were coded in the Conceptual Framework as well.

The aim of the next chapter is thus to perform a comparative case study of the temporal climate framing in governmental communications of the Netherlands and Ireland in 2018-2019. Using the frame orientation as designed by De Boer et al. (2010, p. 504), which was further expanded upon in the previous chapter, the research will consist of an analysis of how the Dutch and Irish climate accords politicise time with regards to climate change, before turning to a comparison of the differences and similarities between these national policies.

3.2. Data

The comparative analysis is performed on the Irish National Adaptation Framework (NAF) written by the Department of Communications, Climate Action & Environment (DCCAE) from 2018 and the Dutch Klimaatakkoord by the Ministerie van Economische Zaken (EZ) from 2019. These two publicly available policy documents were collected from the respective countries’ governmental websites (AZ, 2022; gov.ie, 2025). The documents outline the national climate policy and agreements made to reduce greenhouse gases, aligning national policy with the Paris Agreement and European law. The plans presented in them aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the levels of 1990 by 2030 and to broadly prepare the countries for the effects of climate change in the long term.

As the documents were published in Dutch and English and these are both languages I speak, there was no need for translations (Ehrensberger-Dow, 2014). The analysis therefore consisted of the original data as presented in Annex 1 and 2.

3.3. Considerations

While methodology, theory, and analysis are fundamental for the conduct of any research, it is also important to be mindful of both the ethics and the limitations of any project. Especially as in sociological research sources are often taken directly from human research subjects, the moral implications of any research require reflection (Rogers, 1987; Aguinis & Henle, 2004; Gajjar, 2013).

While human coding guided by prototypes instead of exact terminology allows for greater flexibility of the research and the discovery of frames not originally included in the coding scheme, this also comes at the cost of smaller research samples and therefore lower reliability of the findings (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 108). This is a tradeoff that has to be made, as human coding relies on the personal abilities of the research. However, this is a tradeoff I wish to defend for several reasons.

Primarily, my abilities are limited by time and manpower so an analysis of all (EU) countries included in Germanwatch’s CCPI is not possible at this current moment. Therefore the study is supposed to be a small-scale comparison of temporal climate framing. Secondly, if my abilities therefore constrain the possible research, the data must remain as unaffected by my analysis as possible. Therefore I have elected to analyse two countries whose language I understand, and that hold interesting positions in the CCPI rankings (Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025). The Netherlands, as can be seen in Figure 1, has risen quite a bit in its environmental performance since 2019, while Ireland has had a much more fluctuating ranking.

Of course, it must be noted that these rankings, out of their complete context, do not tell the full story. National performance is largely shaped by the framing of climate change (Pettenger, 2016). Additionally, while the rankings are largely based on national performance, if country A, which years earlier scored lower than country B, suddenly increases its reduction of greenhouse gasses and enacts more sustainable policies, then country B will fall in the rankings as a result.

However, as mentioned, tracking the environmental movements of all countries listed in the CCPI rankings falls beyond the scope of the current research. Therefore the research focuses on Ireland and the Netherlands.

Because of the constraints on the research, it can be argued that the case selection is anywhere between minimal to dismally unrepresentative. This is unfortunately one of the limitations of qualitative research (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 108). However, the value of research on its own is also a reason to conduct academic investigations (Speyer, 2018). While this research paper may not come to any substantial conclusion on the discussed topic, it may continue to add to the ongoing debate on framing.

4. Analysis

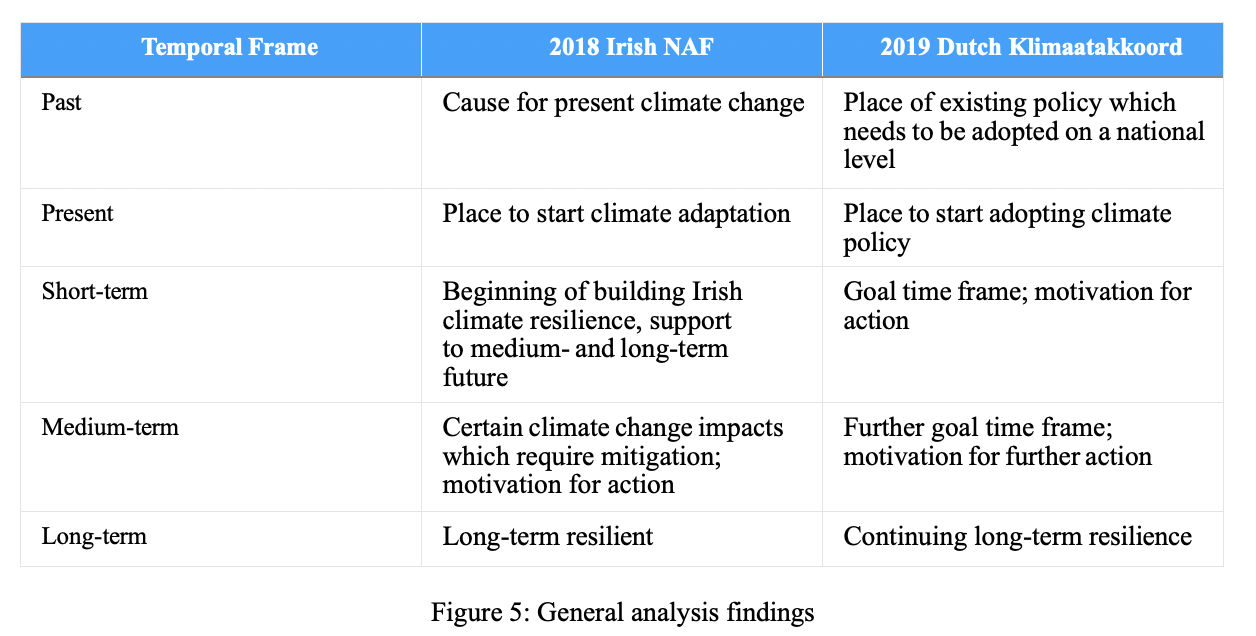

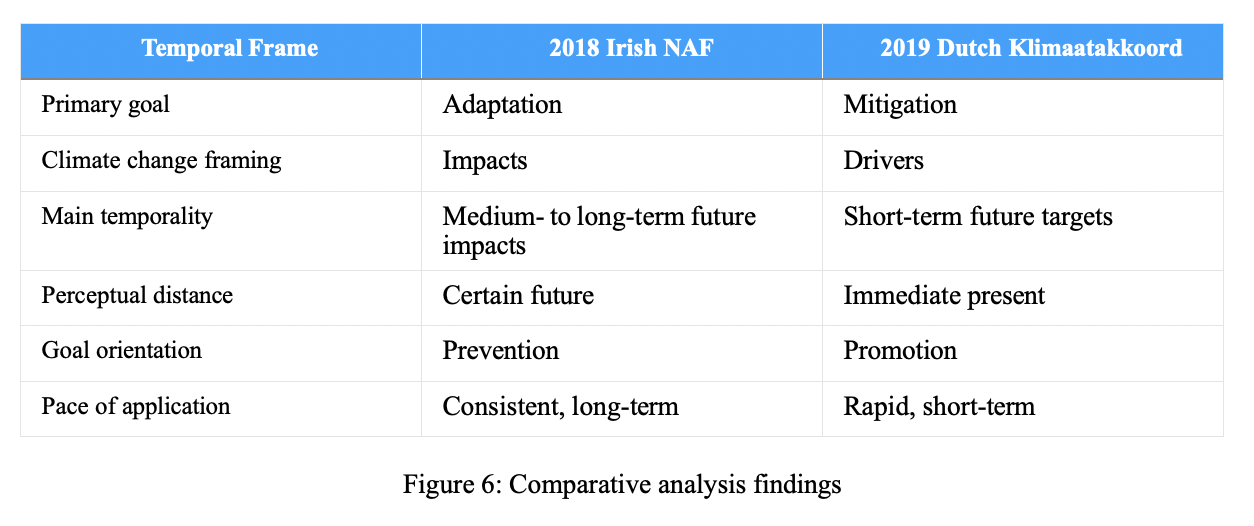

This chapter first considers the Irish National Adoptation Frame (NAF) (DCCAE, 2018), in terms of overall tone, policy proposals, and employed framing. The same is then done to the Dutch Klimaatakkoord (KA) (EZ, 2019). This is followed by a comparison of the similarities and differences between the two pieces of legislation, for the purpose of answering the research question. Figures 5 and 6 shows the findings from the frame analysis of the two documents.

4.1. Ireland

The 2018 Irish NAF has as its primary goal to prepare Ireland for the unavoidable impacts of climate change, as indicated by its title “Planning for a Climate Resilient Ireland”. It is therefore fundamentally an adaptation-focused document. This framing of climate change is also observable in fact that, while it acknowledges that climate change is anthropogenic, the focus of the document is not on the drivers of climate change. Mitigation is instead only mentioned in the context of international policy drivers that impose required adaptation policies, instead of being the core focus of the NAF itself (DCCAE, 2018, p. 102-106).

Because the document assumes that climate impacts will occur, it therefore opts to prepare for the effects, rather than try to prevent them (DCCAE, 2018, p. 9). The NAF thus makes many references to both the already observable as well as projected impacts of climate change on Ireland (DCCAE, 2018, p. 13). These include changes in mean temperature (DCCAE, 2018, p. 25-29) and increases in extreme weather events (DCCAE, 2018, p. 26-28, 34-39). The language which is used for this is largely descriptive and puts a heavy emphasis on Ireland’s vulnerability to change (DCCAE, 2018, p. 3, 13).

The document creates a collaborative multi-sectoral approach to adaptation. The mechanisms to put the Irish response into place rely on legislation such as the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act from 2015, which in turn requires the consideration of the strategy employed by various sectors and local authorities (DCCAE, 2018, p. 31, 41-51). The document also highlights the importance of further research on the effects of climate change on Ireland and the possibilities for adaptation (DCCAE, 2018, p. 54-55).

In terms of its framing of temporality, the main focus in the NAF is on the medium- to long- term future impacts. When the document references the past it is primarily used to establish the cause for present climate trends (DCCAE, 2018, p. 3), which in turn grounds the need for current and future adaptation (DCCAE, 2018, p. 4-5, 41). In the present (2018), adaptation is framed as a process which, although ongoing, needs to start (DCCAE, 2018, p. 4, 7, 34). The NAF thus sets the stage for immediate action. The short-term future frame is used to focus on the beginning of building Irish climate resilience which supports a medium- to long-term future frame. The medium- term frame is used to set expectations and warn of the impacts which should be anticipated and thus protected against (DCCAE, 2018, p. 3-4, 8, 76). The long-term future is less explicitly detailed. It does, however, refer to “long-term resilience” (DCCAE, 2018, p. 7) and preparations for a future beyond 2050 because of climate change’s enduring nature (DCCAE, 2018, p. 21, 64).

The perceptual distance of climate change is in the NAF predominantly in the future, where it poses a challenge. It uses present impacts as a motivator for action. Climate change is framed not as an immediate crisis, but instead as a certainty which requires proactive mitigation responses.

Urgency towards action is derived from framing climate change as an inevitability (DCCAE, 2018, p. 3, 7, 13).

4.2. The Netherlands

The 2019 Dutch KA is mainly a mitigation-focused document, which aims to achieve ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction goals across multiple sectors. While there is a mitigation intent behind the KA’s ambition, this frame remains almost completely left out (EZ, 2019, p. 15). In response to the climate crisis, the KA proposes a highly structured, multi- stakeholder, and comprehensive governance approach (EZ, 2019, p. 9-12). The document strongly emphases shared responsibility and collective action (EZ, 2019, p. 4) and presents multiple well- structured measures to reduce emissions, such as subsidies and a monitoring and evaluation framework (EZ, 2019, p. 11-12, 95-97).

In terms of the framing of temporality, does the KA use the past mainly as a baseline for emission reductions (EZ, 2019, p. 4, 7, 33, 83, 230) and cites various previous agreements as the further foundation for action (EZ, 2019, p. 8). Meanwhile, the document frames itself as an immediate cause for emission reductions and highlights the commitment of the administration of the time to immediate implementation (EZ, 2019, p. 9-10). In the document, the short-term future (2019-2030) is the most prominent temporal frame, as its main purpose is to set out policy measures to achieve the goal of a 49% GHG emission reduction by 2030 compared to 1990 (EZ, 2019, p. 4, 7).

The KA has detailed sectoral targets and policy instruments planned for this timeframe (EZ, 2019, p. 15, 45, 83, 117, 157, 185). The urgency of climate action is linked to the achievement of this target within its timeframe. While 2030 is the immediate focus of the KA, the document also shows its intention to align with the EU’s longer-term goal of climate neutrality by 2050 (EZ, 2019, p. 4). 2030 is therefore framed as an essential step towards further emission reductions. This vision for 2050 creates an implicit extension into a sustainable future beyond then, in which the Netherlands will continue to innovate and adapt (EZ, 2019, p. 7).

The KA’s framing of temporality makes action towards climate change mitigation an urgent matter to be achieved in an immediate and actionable timeframe (2030). While the urgency for action in the document itself comes from having to adhere to EU legislation (EZ, 2019, p. 4), this implicitly refers to the threats posed by climate change as well as the risk the Netherlands is at given the country’s geographic position. The history of the Netherlands (Hoeksema, 2007, p. 114) can also explain why the KA details its plan to lobby in the Council of Europe for stricter reduction goals (EZ, 2019, p. 4).

Generally, the KA has a promotion-focused goal orientation. While the ultimate goal is to prevent climate change, the document itself primarily frames action in terms of achieving ambitious reduction targets, while at the same time fostering social and economic prosperity (EZ, 2019, p.

15-184). The language used highlights opportunities and benefits to cooperation and action, such as the creation of new industries and the achievement of a safe and sustainable state for all citizens (EZ, 2019, p. 15-16). This might be attributed to the KA being intended as the first implementation of the Dutch Climate law (EZ, 2019, p. 8).

These findings are summarised in Figures 5 and 6.

4.3. Comparison

Looking at the two documents side by side, there are very obvious differences. First and foremost; the primary goals. Both documents allude to the most important framing in their title. The NAF is meant to guide the adaptation of Ireland to the effects of climate change. Its main focus is therefore on addressing the impacts of climate change.

The KA has a much less explicit adaptation framework. It only references the direct effects of climate change in its introduction. The challenge climate change poses is mainly alluded to through references to EU climate law, such as the Paris Agreement. Instead, it primarily focuses on mitigation and addresses drivers of climate change. The KA emphasises extensive dialogue, consensus-building, and partnership between stakeholders for the achievement of common goals, as it maintains that because of the remaining time between the present (2019) and the future where the effects of climate change become disastrous still allows for political action. The NAF's primary focus on adaptation compared to the KA's on mitigation represent their distinct goal orientations within framing theory. This directly influences how both nations guide their decision-making on climate action (De Boer et al., 2010).

The second main difference is the perceptual distances of climate change in both documents, which is a critical element to the perception and operationalisation of time (Pahl et al., 2014). The NAF predominantly places the challenge in the future and is thus focused on the medium- to long- term future. This is framed as the moment when climate change’s impacts will become much more severe. The KA instead highlights the short-term future temporal aspects related to climate change and argues that action is needed in that time specifically. However, it also frames the medium-term future as an important temporality, as this time will require further emission mitigation efforts. So while both documents stress the importance of immediate action, the temporal cause is a lot further away in Irish than in Dutch framing.

These different framings of climate change’s temporality affect the pace of applying the proposed legislation. Ireland’s pace of application, although less explicit compared to that of the Netherlands, is much more consistent and focused on a longer-term, while the Dutch KA proposes rapid, short-term legislation application.

In summary, Ireland’s NAF largely frames climate change through the lens of inevitable, escalating threats which exist in the future. To address this challenge it necessitates immediate and continuous adaptation that prevents further adverse results to Irish society. Urgency comes from the certainty attached to the temporality of climate change. The Dutch KA also frames climate action as urgent and necessitating immediate action. However, this document prioritises the complete mitigation of emissions and the achievement of climate neutrality by 2050. This means that the Netherlands uses framing theory to advocate for mitigating (further) adverse climate change, while Ireland frames these as inevitable and instead uses the threat of temporality to promote adaptation. These differences highlight the paradoxical temporalities inherent to climate change and show that urgency can come from both distant certainty and immediate deadlines (Garrard, 2019)

In essence, the Dutch temporal framing is a countdown to a crucial environmental deadline, while the Irish temporal framing is a continuous, evolving journey of preparedness for a certainly impactful future.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this research paper aimed to answer the research question “How did Ireland and the Netherlands temporally frame the climate crisis in comparison after the Paris Agreement?”. It investigated the way climate change and its temporality were framed in the 2018 Irish National Adaptation Framework (NAF) and the 2019 Dutch Klimaatakkoord (KA) through a frame analysis. Based on the findings expanded upon in the previous chapter, the following conclusions can be made.

Ireland and the Netherlands framed climate change very differently in 2018-2019. Ireland framed the impacts of climate change as the main challenge, the Netherlands instead posed its drivers as the problem. In terms of temporality, Ireland saw climate change as an issue of the medium- to long-term future, while the Netherlands posed it as a short-term future problem. These temporal frames affected how and with what tempo the two countries proposed to tackle the challenge, as well as what deadlines they connected to the proposed policy, which shows how framing guides decision-making on climate change (De Boer et al., 2010).

The performed analysis, together with the literature review, shows that time and climate change are connected (Chakrabarty, 2020; Winter, 2020; Folkers, 2021). Therefore, policies created to deal with the climate crisis also must be aware of the temporal dimensions of the problem.

Successful climate policy incorporates a temporal frame (Pahl et al., 2014).

It is tempting, in light of both the countries’ CCPI rankings after 2019, to conclude what temporal framing of the climate crisis creates the most effective climate policies. As can be seen in Figure 1, directly after the implementation of the KA and NAF, the Netherlands’ CCPI ranking plateaued, while the Irish CCPI ranking went down (Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025) (see Figure 1).

However, it is important to also note that this research was limited. Primarily in temporal focus and case selection. The paper, for example, did not include an analysis of Irish and Dutch climate adaptation policies from before or after 2018-2019. This means that the research was conducted in a vacuum of context, and the changes to CCPI rankings (Chong & Druckman, 2007; Germanwatch e.V, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025) cannot be fully subscribed to the policy documents from the investigated timeframe. It is possible that in 2021 new frameworks were created that boosted the effectiveness of Dutch climate action and hindered Irish action. Similarly, policies that effectively or ineffectively impacted climate performance might already have been in place at the time of the documents’ publication (Coghlan, 2007; Torney, 2017). However, this final argument should be slightly negated, as the NAF and KA were the first Irish and Dutch attempts at implementing the Paris Agreement (DDCAE, 2018, p. x; EZ, 2019, p. 8).

Therefore, specifically, the time after the creation of both the analysed documents is an interesting avenue for future research. This can revisit the temporal framing of climate change on a national and European level, expand the investigated time frame, and include considerations of changing political dynamics inside democracies. An expansion of research avenues may draw more concrete conclusions about the influence of temporal framing on climate change adaptation policies (Vink et al., 2012; Stanley et al., 2021; Herberz et al., 2023). Investigating these internal dynamics could show how politics of time not just influence policy creation, but also the very execution and projection of climate governance (Vink et al., 2012).

In sum, however, In 2018-2019, Ireland and the Netherlands had quite different framings of both climate change and its temporality. These were not merely descriptive choices, but direct manifestations of the politics of time. The findings suggest that differences in national approaches to climate change are deeply embedded in the political framings of time (Garrard, 2019; Herberz et al., 2023; Stanley et al., 2021). Effective climate action may therefore require nuanced adaptation and mitigation plans, which account for national and historic context.

References

Aguinis, H., & Henle, C. A. (2004). Ethics in research. Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology, 34-56.

Ansari, S., et al. (2013). Constructing a climate change logic: An institutional perspective on the “tragedy of the commons”. Organization Science, 24(4), 1014-1040.

Brace, C., & Geoghegan, H. (2010). Human geographies of climate change: Landscape, temporality, and lay knowledges. Progress in Human Geography, 35(3), 284–302. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0309132510376259

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Coghlan, O. (2007). Irish Climate-Change Policy from Kyoto to the Carbon Tax: a Two-level Game Analysis of the Interplay of Knowledge and Power. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 18(1), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.3318/isia.2007.18.131

Daviter, F. (2007). POLICY FRAMING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION. Journal of European Public Policy, 14(4), 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701314474

De Boer, J., et al. (2010). Frame-based guide to situated decision-making on climate change. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 502-510.

Department of Communications, Climate Action & Environment (DCCAE). (2018). National Adaptation Framework: Planning for a Climate Resilient Ireland. https://assets.gov.ie/static/ documents/national-adaptation-framework-c3365ac1-e48c-486b-a7b9-b7af6d842b2f.pdf

De Roeck, F., et al. (2017). Framing the climate-development nexus in the European Union. Third World Thematics a TWQ Journal, 1(4), 437–453. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/23802014.2016.1286947

Dewulf, A. (2013). Contrasting frames in policy debates on climate change adaptation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Climate Change, 4(4), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.227

Dirikx, A., & Gelders, D. (2010). To frame is to explain: A deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Understanding of Science, 19(6), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662509352044

Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2014). Challenges of translation process research at the workplace. MonTI- Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, 2014(Special Issue), 355-383.

Edensor, T., et al. (2019). Time, temporality and environmental change. Geoforum, 108, 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.003

European Commission (EC): Directorate-General for Climate Action (n.d.). Climate Action: EU competences in the field of climate action. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu- competences-field-climate-action_en

Folkers, A. (2021). Fossil modernity: The materiality of acceleration, slow violence, and ecological futures. Time & Society, 30(2), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463x20987965

Gajjar, D. (2013). Ethical consideration in research. Education, 2(7), 8-15.

Garrard, G. (2019). Never too soon, always too late: Reflections on climate temporality. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Climate Change, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.605

Germanwatch e.V. (2019). Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://newclimate.org/ sites/default/files/2018/12/CCPI-2019-Results.pdf

Germanwatch e.V. (2020). Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://ccpi.org/wp- content/uploads/ccpi-2020-results-the_climate_change_performance_index-1.pdf

Germanwatch e.V. (2021). Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://ccpi.org/ download/the-climate-change-performance-index-2021/

Germanwatch e.V. (2022). Downloads | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://ccpi.org/wp- content/uploads/CCPI-2022-Results-1.pdf

Germanwatch e.V. (2023). Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https:// www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/ccpi-ksi-2023-kurzfassung.pdf

Germanwatch e.V. (2024). Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://ccpi.org/ ranking/

Germanwatch e.V. (2025) Ranking | Climate Change Performance Index. Climate Change Performance Index | the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Is a Scoring System Designed to Enhance Transparency in International Climate Politics. https://ccpi.org/ ranking/

gov.ie. (2025). National Adaptation Framework (NAF). https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of- climate-energy-and-the-environment/publications/national-adaptation-framework-naf/ Hänggli, R., & Kriesi, H. (2012). Frame construction and frame Promotion (Strategic framing

choices). American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 260–278. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0002764211426325

Hardy, J. T. (2003). Climate change: causes, effects, and solutions. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/ BA62526790

Herberz, M., et al. (2023). The impact of perceived partisanship on climate policy support: A conceptual replication and extension of the temporal framing effect. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101972

Hilson, C. (2018). Framing time in climate change litigation. Oñati Socio-legal Series, 9(9(3)), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1063

Hoeksema, R. J. (2007). Three stages in the history of land reclamation in the Netherlands.

Irrigation and Drainage, 56(S1), S113–S126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.340

Kang, S., et al. (2023). Climate change and the challenge to liberalism. Global Constitutionalism, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045381722000314

Kennedy, R. (2011). Climate change law and policy in Ireland. SSRN Electronic Journal. https:// aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/10379/2282/1/ Climate%20change%20law%20in%20Ireland.doc

Kruitwagen, S., et al. (2009). Pragmatics of Policy: The compliance of Dutch environmental policy instruments to European Union standards. Environmental Management, 43(4), 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9248-6

Lamkowsky, M., et al. (2024). Financial barriers to reducing nitrogen pollution in Dutch dairy farms. EuroChoices. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692x.12453

Lewis, S. L., & Maslin, M. A. (2015). Defining the anthropocene. Nature, 519(7542), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258

Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms?. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 40(2), 235-258.