Geo Jurisprudence: A Chimera of Law, Cartography and Geopolitics

Written by Milou Vlaskamp

Milou is a graduate of the Research Master’s in Modern History & International Relations and LLM Public International Law at the University of Groningen. Her research interests focus on transitional justice, legal theory and international criminal law. This essay was submitted in January 2024 for the Research Seminar Geopolitical Ideas and International History.

Geo Jurisprudence: A Chimera of Law, Cartography and Geopolitics

The Geojurisprudential Thought of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg

ABSTRACT. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg developed the concept of geo jurisprudence which argued that legal developments were rooted in geopolitical factors. These new insights were depicted through cartography to depict power relations between states. The geo jurisprudential endeavor therefore was a chimeric effort between geopolitics, legal theory and cartography in developing a right to space. The work of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg has been underexplored within English Academia, through a main analysis of his work The Great Power’s Geo-Jurisprudentially Viewed the debates surrounding geo jurisprudence during the Weimar Era and its role within German Geopolitics is explored. A geo jurisprudential approach portrays Germany as an inhibited power that reflects the contemporary stance regarding the German state’s position post World War 1 and provides a rationale for German expansion.

Keywords: Geojurisprudence, Manfred Langhaus-Ratzeburg, Geopolitics, German Legal Theory,

1. Introduction

German geopolitical discourse flourished in the inter-war period of the Weimar Republic. This period has been described as an era of “crucible intellectual innovation” in fields from political theory to legal theory [1]. The so-called Geowissenschaften were widely discussed and debated within academic circles, including the field of geopolitics [2]. In this context it was characterized by environmental determinism, holding the assumption that political actors needed to react to the environment to ensure prosperity [3]. Whilst the geopolitical debates in the interwar years in Germany as well as elsewhere have received scholarly attention, other endeavors within the Geowissenschaften such as Geojurisprudenz (Geojurisprudence) have not. Especially within English academia. Therefore, there is merit in considering these debates and how they interacted within the wider geopolitical discourse at the time.

Geojurisprudenz refers to the engagement of geopolitical thought with that of the legal theoretical field. The German geopolitical discourse notably attempted to integrate a wide variety of fields, such as those of history and culture as well as the legal field. The latter in the form of geo jurisprudence attempted to explain jurisprudence and legal structures through geopolitical terms. Concepts such as Lebensraum and Mitteleuropa, associated with ‘German Geopolitics’ are present in the field of Geojurisprudenz to argue for a new type of jurisprudence which establishes a right to both space and soil [4]. For a geo-jurist world powers have natural rights to their living space [5].

Geojurisprudential thought is present in the work of Carl Schmitt, one of the most prominent legal and geopolitical thinkers of the Weimar Republic but also of the Nationalsozialismus. The term and methodology of Geojurisprudential thinking however did not originate from the work of Carl Schmitt, instead, a lesser-known yet important thinker to consider, Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg first coined the term Geojurisprudenz [6]. The endeavor towards geo jurisprudence reflected legalistic thinking and the development of a right to space based on geopolitics.

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg draws on key geopolitical thinkers of the time to develop geo jurisprudential thinking. Legal theoreticians, geopoliticians and political thinkers at the time engaged with the emerging research agenda of geo jurisprudence, indicating that there was a debate about this field in the Weimar Republik. Geo Jurisprudence was described shortly after the Second World War as being a National Socialist theory of international law which was based on an idea of ‘spatial purity’ [7].

Therefore, an exploration into how geo jurisprudential discourse constructed a German interpretation of international law merits consideration. Through taking a critical approach, especially with regards to legal theory, general questions such as what power structures are present in the geo jurisprudential debate in the Weimar Republic can be asked. This also includes questions of how international law is represented and discussed within the geo jurisprudential debate.

The main analysis undertaken is a primary analysis of the work of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg as a pioneer of the geo jurisprudential field [8]. As a term, geo jurisprudence was first introduced in Begriff und Aufgaben der Geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Concepts and Tasks of Geographic Jurisprudence).

This was further developed in his work Die Großen Mächte: Geojuristich Betrachtet (The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially), which will be the main focus of analysis. Supporting this analysis several contemporary reviews of the work published, or other works reviewed by Langhans-Ratzeburg have been included as primary sources. Due to a lack of accessibility of some of the main works of Langhans-Ratzeburg, the scope of this research has been limited to what was accessible. Including contemporary reviews to an extent mitigates this inaccessibility and also provides insight into how the ideas and thoughts of Langhans-Ratzeburg were received within the geopolitical discourse at the time. This allows for the relationship between international law and geopolitics to be discussed.

To answer the questions, the context in which Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg was writing will first be considered. The general discourse of ‘German Geopolitics’ and its foundations will be discussed. Moreover, Manfred Langhans Ratzeburg as a figure will also be described based on available archival material and other secondary sources.

This will be followed by a discussion of his work and thoughts which will subsequently be contextualized within the wider geopolitical debate and with other prominent legal thinkers such as Carl Schmitt.

2. German Geopolitics and the Weimar Period

‘Geopolitik’ is a concept which invoked in the context of a post second world war German discourse would have been met with an awkward silence. Nevertheless, the German geopolitical discourse was the first of its kind in which scholars oriented themselves around the concept of ‘geopolitics’ as coined by Rudolf Kjellen in 1899 [9]. According to Rainer Sprengel, the concept of geopolitics indicates an ambivalence with the connection of the word ‘geo’ and ‘politics’. This connection thus allows for a starting point to be political analysis or geoanalysis [10].

On the other hand, Sprengel points out that geographers believed that the field of traditional political geography already had a sufficient starting point and closeness to geopolitics. This latter conceptual distinction was a constant debate in the 20s and 30s amongst scholars in Germany. Characteristic of geopolitical thought in Germany at this time was its environmentally deterministic nature, scholars held the assumption that political actors needed to react to the environment to ensure prosperity [11].

The main question that geopolitics draws attention to is the role that territory and space play within international politics [12]. Consequently, due to this attention and emphasis on territory and space, David Criekemans has pointed out that geopolitical research traditions are influenced by the particular space and time in which individual scholars worked [13]. For example, German geopolitical discourse was largely influenced by geographical determinism due to the scholarly contributions it has developed [14].

The concept of “Lebensraum” developed by Friedrich Ratzel played a significant role in these developments Ratzel argued that the strength of a state can be found in its Raum (space) and Lage (position) [15]. These two factors were important in the “kampf ums dasein” meaning they were important for the existence of a state [16]. Karl Haushofer in the context of a defeated Germany after World War 1 took up this concept as an analytical framework to understand the position of Germany in the international sphere [17]. A key aspect was the central position that Germany had, its Mittellage [18]. Germany was seen as being a great power constrained by the post-Versailles settlements.

In the period of 1918 to 1933 great amounts of geopolitical literature were produced, especially in the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik [19]. According to Criekemans, it was in 1934-44 that an ethno-nationalistic variant of “Geopolitik” was developed and ceased to concern itself with the relationship between territoriality and politics [20]. Moreover, Criekemans identifies two distortions of the original concept of geopolitics, one of these being the application of the concept of geopolitics to a wider area of application equalling political science with geopolitics [21].

The second distortion was the aforementioned ethno-nationalization of the concept most associated with the Nationalist Socialist Party. Haushofer played a prominent role in the establishment of a German geopolitical discourse and 1924 established the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfGp) [22] alongside Erich Obst, Hermann Lautensach and Fritz Termer [23]. It is only in 1932 that Haushofer became the sole editor of the journal, due to disagreements about the political course the journal was taking and interference from the Nazi-orientated publisher Kurt Vowinckel [24]. Between 1924 and 1944 a total of 1269 publications appeared in the ZfGp, and a total of 619 persons contributed [25]. Rainer Sprengel conducted a comprehensive analysis of the contributions made within the journal and was able to sketch a clear evolution of the journal and its contributions. Only 42 persons made more than five contributions to the journal, yielding a total of 322 contributions [26]. Manfred Langhans Ratzeburg made a total of 5 contributions to the journal [27].

These contributions were made between 1927 and 1931. According to Sprenger the period of 1924-1928 marked a rapid awakening of geopolitical discourse [28]. Which was marked by an increase of 800 pages per year to 1200, and a production of 4000 copies of the journal [29]. Sprenger described this as a widening and consolidation of the discourse [30]. From 1928-1932 the journal was in a phase of crisis as the production and reach had almost halved, this was due to the aforementioned political disagreements between the editors of the journal. Consequently, in 1933 the journal took a more national socialist orientation and increased its production and scope again.

These contextual factors are relevant in conducting a thorough and accurate analysis of the work of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and the contributions of geo jurisprudence within the wider geopolitical debate. To understand the contributions made by Langhans-Ratzeburg it is also necessary to understand both his personal and academic background. Based on archival material and secondary sources, an insight into this can be gained.

3. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg

3.1. Biographical Details

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg (1901-92) was born in Gotha, Germany as a son of the cartographer and geographer Paul Langhans (1867-1952) [31]. Whilst Langhans-Ratzeburg obtained a doctorate and training in Law it is not surprising that he also held an interest in geopolitical thought. His father, Paul Langhans was a well-known geographer and cartographer who edited Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen which was one of the most prestigious geographical journals in the Weimar Period [32].

Moreover, Paul Langhans has been described as an influential expert on “German nationalist cartography” and translated “the völkische ideology of the Pan-German League into cartographic projects” [33], which was influenced by Ratzel’s concept of Lebensraum [34]. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg as noted by David Murphy undoubtedly was to an extent influenced by his father’s work, more importantly, Langhans-Ratzeburg began his academic career by publishing in the journal edited by his father [35]. It is here that Langhans-Ratzeburg began to discuss and develop geojurisprudence.

This included the development of a ‘geojuristic’ cartography in which the actual relative power of a state or people would be depicted [36]. According to Alain Pottage, this reflected a wider interest in the relations between geography and normativity [37].

3.2. General works

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg published a total of 6 works and produced cartographic depictions to support his geojuristic arguments. The most prominent work discussing geojurisprudence is Begriff und Aufgaben der Geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz) (Concepts and Tasks of Geographic Jurisprudence), in which legal theory was linked to geography, cartography and geopolitics [38].

In 1929 Langhans-Ratzeburg applied geo jurisprudential thinking to study the Wolgagermans (Volgadeutschen) in which he pointed out that the Volga Germans were isolated geographically from their homeland Germany [39]. However, due to increased legal autonomy received from the Bolshevik regime, they could preserve their cultural integrity, thus law triumphed over geographic elements in protecting the lebensraum of the Volga Germans [40].

The last major work written during the Weimar Era, and also the work mainly analyzed, is The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially, in which Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that Germany can be considered to be one of the great powers, albeit handicapped due to concessions made in the first world war. It is due to its natural resources, population and development that Germany can be considered as a great power [41]. The position of Germany, geopolitical and geo jurisprudentially is discussed within the book.

Due to accessibility limitations, the main focus will be on The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially. Alongside an analysis of this work, reviews written at the time of general works by Langhans-Ratzeburg are also considered.

4. Law, Geopolitics and Geo Jurisprudence: Carl Schmitt, Karl Haushofer and Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg is considered to be the most prolific and articulate proponent of geo jurisprudence [42]. Geo Jurisprudence was defined by Langhans-Ratzeburg in his work Concepts and Tasks of Geographic Jurisprudence, as being a branch of jurisprudence which explained or illustrated the results of juridical research through cartographic or geographic arguments [43].

A geo jurisprudential approach argues that the judicial organization of a state and its position vis-a-vis other States is determined by its geographical position and conditions. Thus, geo jurisprudence claimed a geo deterministic development of the law [44]. It is an endeavor in which the sources of law are sought within the geographic conditions and position of a state. David Murphy points out that the efforts of Langhan’s Ratzeburg can be considered within the wider relativistic legal tradition existing in Germany since the 19th Century [45]. Moreover, this legal theorizing was in line with that of the Grossraum legal theorizing of Carl Schmitt. American Political Scientist Andrew Gygory in 1944 claimed that Schmitt was the “foremost exponent” [46] of geo jurisprudence, ignoring the contributions made by Manfred-Langhans Ratzeburg [47]. Karl Haushofer, one of the most eminent German geopoliticians [48], praised the idea of a geo jurisprudential method as he saw German legal studies and their lack of geographical grounding as misleading Germans in what their struggles and challenges were post World War 1 [49].

He also contributed an article to the geo jurisprudential debate in 1928 [50]. William Hooker has categorized such legal geopolitical ideas as being a significant branch of anti-positivist legal theory [51]. To understand the contributions made by Langhans-Ratzeburg and his approach to international law the work of Carl Schmitt must be considered as both applied their theories to interstate relations and international law.

5. German Legal Theorizing: Situating Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Carl Schmitt

A key aspect of the legal and geo jurisprudential thinking of Carl Schmitt is the concept of Grossraum. The Nomos of the Earth, although written in 1950, has been engaged with most by scholars tracing the international legal theory of Schmitt. Robert Howse, argues that it is his works on political theory, Political Theology and The Concept of the Political, which provide the most important concepts and arguments for understanding his international legal thoughts [52]. Moreover, Howse points out that these works are “attacks on liberal constitutionalism in the Weimar Republic, as well as liberalism and the rule of law as such, and only secondarily or derivatively concerned with international order” [53]. According to Benno Gerhard Teschke, The Nomos presents an alternative vision of a future world order which revolves around the concept of Großraum [54]. Schmitt’s legal theorizing objected to “the placeless spatiality of legal positivism”, through his writings he suggested an ordering of the world according to geopolitics [55]. Law therefore is determined and tied to spatiality and geographical conditions [56]. This echoes the geo jurisprudential thinking of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg who departed from the claim that law developed geo deterministically.

A geographic international law, for Langhans-Ratzeburg, was a source of geopolitical knowledge as it was “the essence of geopolitics to investigate political processes through a dynamic method of consideration within the chorographic perspective of earth dependency, thus it treats primarily international legal processes” [57]. Space and geography is understood by both Langhans-Ratzeburg and Schmitt as “the precondition and origin of the law” [58]. Andrew Gyorgy argued that a central argument of geo jurisprudence was its introduction of “a new principle of power politics, that of the right to space” [59].

In his contemporary critique of Geo Jurisprudence, Adolf Grabowsky stated that it is only a legal recognition of relations between space and law [60]. Grabowsky furthermore emphasizes that a geo jurisprudential effort can only be conducted by a jurist [61]. Much like geoeconomics by an economist and geomedicine by a medical doctor [62]. Both Langhans-Ratzeburg and Schmitt are jurists who combine geopolitical thinking with legal theory and the legal field. Therefore geojurists argue that world powers have a natural right to their Lebensraum. A key aspect of this legal theorizing is that it departs from the natural law tradition, which is based on the highest principles of morality which humanity strives for and can be deduced through reason [63]. Natural law is a rationalistic endeavor which provides the basis of jus gentium [64], therefore it forms the basis of international law [65]. Whilst Langhans-Ratzeburg and Schmitt are both writing more within the framework of this general legal tradition, it is also influenced by the general context in which they were writing.

Legal theorizing and thinking during the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the National Socialist period saw a revival of natural law. Positivist law views the validity of law and law itself being derived from a verifiable source [66]. A prominent contemporary proponent of positivist law, also of an international positivist legal order, was Hans Kelsen who argued that all laws could be traced back to a grundnorm. Legal scholarship during the Weimar Republic advocated a moderate form of positivism with a focus on statutes and legislature, however, disputes amongst notably Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt “drove nails into the coffin for the juridical method of public law positivism [67]. Instead, there was a renewal of natural law. However, this did not encompass the traditional content of natural law, instead as Stephan Kirste argues it was being replaced by a National Socialist legal ideology [68]. This “version” of natural law did have one aspect in common with the “original” natural law, namely its “firm belief that there is an absolute, eternal law, a law that flows from the essence [Wesen] of a naturally given subject” [69].

This took the form of a naturalist ideology which stressed the unity of those who shared a common German language, and history and gave a natural right to those belonging to this group to conquer space [70]. It is in this context and thinking about natural law that both Langhans-Ratzeburg and Schmitt predominantly argued. Taking note of these theoretical assumptions and influences allows for a critical analysis of The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially and how the international legal order is portrayed.

6. The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially

The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially was published in 1931, written by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg; in the preface, it is stated that a geo jurisprudential analysis of the great powers will be explored [71]. From a geographical perspective, the political and legal institutions of States and colonies as well as their relationship are explained and portrayed cartographically. The main argument drawn from this geojuristic analysis is that Germany remains one of the great powers due to its geographic position in Mitteleuropa, its natural resources and its population [72]. It was due to its position in the international legal order that it was constrained. Within the geo jurisprudential analysis of Germany several concepts such as Lebensraum, Mitteleuropa and Erdgebundenheit feature. These concepts are also relevant in the geojuristical analysis of the other great powers. Notably, Langhans-Ratzeburg clarifies in the preface that “the author is of the belief that the chosen order of analysis of States reflects the present degree of significance the individual states have (own translation.)” [73]. The geojuristic analysis of states is therefore as follows, the United States of America,the British Empire, France, the USSR, Japan, Italy and lastly Germany.

The chapter title for the geo jurisprudential analysis of Germany is indicative of the argument that Germany is an inhibited power, translated it is titled “The Inhibited/Stunted Great Power of Germany” [74]. For Langhans-Ratzeburg there lies new knowledge to be gained from a geo jurisprudential analysis, especially in revealing a state’s ‘true’ sphere of power. Power is not adequately understood by lawyers according to Langhans-Ratzeburg, instead, they only focus on one state and fail to see the relations between states, relations between their colonies and other spaces they exercise their influence. Only through a geo jurisprudential consideration can the tatsächlicher Machtbereich, the real sphere of influence be determined.

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg provides a comprehensive analysis of the spheres of influence of each of the great powers. The United States is considered to be the ‘greatest’ and most significant power as it is the first to be analyzed. A key aspect drawn out from the analysis of Langhans-Ratzeburg is the influence of man or nature concerning geopolitical conditions. For example, the creation and organization of the United States in its current form was wanted both by “Raum” (space) and by man [75].

The American states are by legal status equal even though they differ significantly both geographically in terms of space and natural resources as well as demographically. This is different for the legal relationship of the US territories to that of the US, Langhans-Ratzeburg gives the example of Alaska being an organized territory whilst Hawaii is an incorporated territory. The answer to these different legal relationships lies in their geopolitical circumstances [76]. The US can increase its influence and obtain geopolitically strategic territories through engaging in different forms of legal relationships with other territories, the form of legal relationship is determined by these geopolitical factors [77]. Precisely what and how these geopolitical factors affect the legal relationships and determine these are not explicitly identified.

This lack of clear analysis is also present in the “textbook” example for an application of the geo jurisprudential method of application to the British Empire. Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that the British Empire provides an excellent example of why the geo jurisprudential method can yield new geopolitical insights. According to him “ the living Right of a State system cannot be viewed purely legal or through its legal history, instead one needs to understand that one only gains knowledge of the empire’s problems when one understands the influence of land and space on the constitution is properly taken into account” [78]. Here Langhans-Ratzeburg emphasizes the concept of Erdgebundenheit with constitutional law. In this view, constitutional developments were geographically determined [79].

This Erdgebundenheit of the constitutional organization is emphasized in the analysis of why certain great powers are organized centralized and others decentralized. Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that this decision is based on geopolitical factors, most notably the existence of a Sammelraum, a gathering space [80].

The French state is considered to be a centralized system in which its constituents and colonies have the same legal status in relation to France, there are no different ‘forms’ or legal structures of power. Instead, the power of the French state emanates from Paris, its geographic center (Mittelpunkt) due to the river networks [81]. Therefore Paris represents a Zentralraum (Central Space) for trade and travel and more importantly this allows for the idea of a national unity due to there being a Sammelraum [82]. The USSR is also considered to be a centralized power that achieved this through the unity of the Russian space.

Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that whilst the USSR on paper might be a ‘union’ in reality it acts as one state due to this unity of Russian Space. This legal ordering is due to geopolitical factors, as in France it is the rivers that create a Mittelpunkt. Moreover, Langhans-Ratzeburg points out that the Soviet Union has expressed a desire to expand as “ the USSR does not want to remain in its current demarcations” [83]. Instead, it wishes to expand by including more “Rätestaaten” through revolutions [84].

Manfred-Langhans Ratzeburg through a geojuristical analysis identifies that the German state needed to be organized in a decentralized manner with a particularistic brand of jurisprudence [85].

This need for a decentralized organization is due to the “Naturausstatung” [86] of the German living space, additionally its rivers do not lead to a natural and centralized point of power [87]. Instead, it is naturally equipped to be a decentralized state [88]. Echoing both Kjellen and Haushofer, who are explicitly mentioned in the preface, Langhans-Ratzeburg takes the stance that Germany is an inhibited great power as it is not able to expand its power [89]. The German state does not exert any influence on colonial or extraterritorial places nor peoples. However, Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that there does remain a will of the German people to expand [90]. This will to expand combined with the geopolitical situation of Germany still made it a great power. The concept of Mitteleuropa features prominently in the arguments presented as to why Germany was still to be considered a great power, although constrained.

‘Mitteleuropa’ refers to the geographical space that is now often termed ‘Central Europe’, though within Weimar discourse it has been used to refer to a wide variety of states in this geographic region. Henry Cord Meyer has pointed out that the term is a product of German geopolitical thought [92].

Therefore, it represents certain conceptions and solutions for the problems facing the states of Mitteleuropa. For Langhans-Ratzeburg Germany was considered to be the biggest state in Mitteleuropa [93]. Moreover, Langhans-Ratzeburg argues that due to the geographic situation of Germany being in Mitteleuropa, it provides the least resistance to the ideologies of Fascism from the south, Bolshevism from the west and democratic-parliamentary systems to the east [94]. Germany thus lies at the crossroads of the “three space-seeking modern political movements” [95]. Langhans-Ratzeburg presents Germany as a constrained nation, echoing the perspectives of Kjellen and Haushofer. The latter argued that Germany had been prevented from being a great power [96]. A geo jurisprudential analysis leads to Langhans-Ratzeburg concluding that Germany is constrained in seeking its own natural space, moreover, its living space is at a crossroads of three different political ideologies and consequently legal and political systems. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg states that the Nationalsozialismus is a “gestalt” (form) of Italian Fascism and represents an intellectual danger to the parliamentary-democracy of the Weimar Republic [97].

Nationalsozialismus gained popularity according to Langhans-Ratzeburg because it concerns a “wholly new German thought” [98]. It is the geo jurisprudential situation of Germany lying in Mitteleuropa that makes it a ‘battleground’ for these different political ideologies. Moreover, due to its position, population and natural resources, Langhans-Ratzeburg considered Germany to be an inhibited power. This inhibited state was due to its position in the international legal sphere, a consequence of the Allied defeat in World War 1 [99].

The international legal order according to Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg is influenced and determined by the geopolitical conditions within a state. The organization of a state and its subsequent relations to outside territories are dependent on the geopolitical composition of the great power as well as the space that is being influenced. Through a geojuristic analysis of how the great powers are legally organized and their legal relations with colonies and extraterritorial states, Langhans-Ratzeburg highlights the real sphere of influence of each state. Here cartography plays a significant role as it allows for a depiction of de jure and de facto power in the international legal sphere at the time.

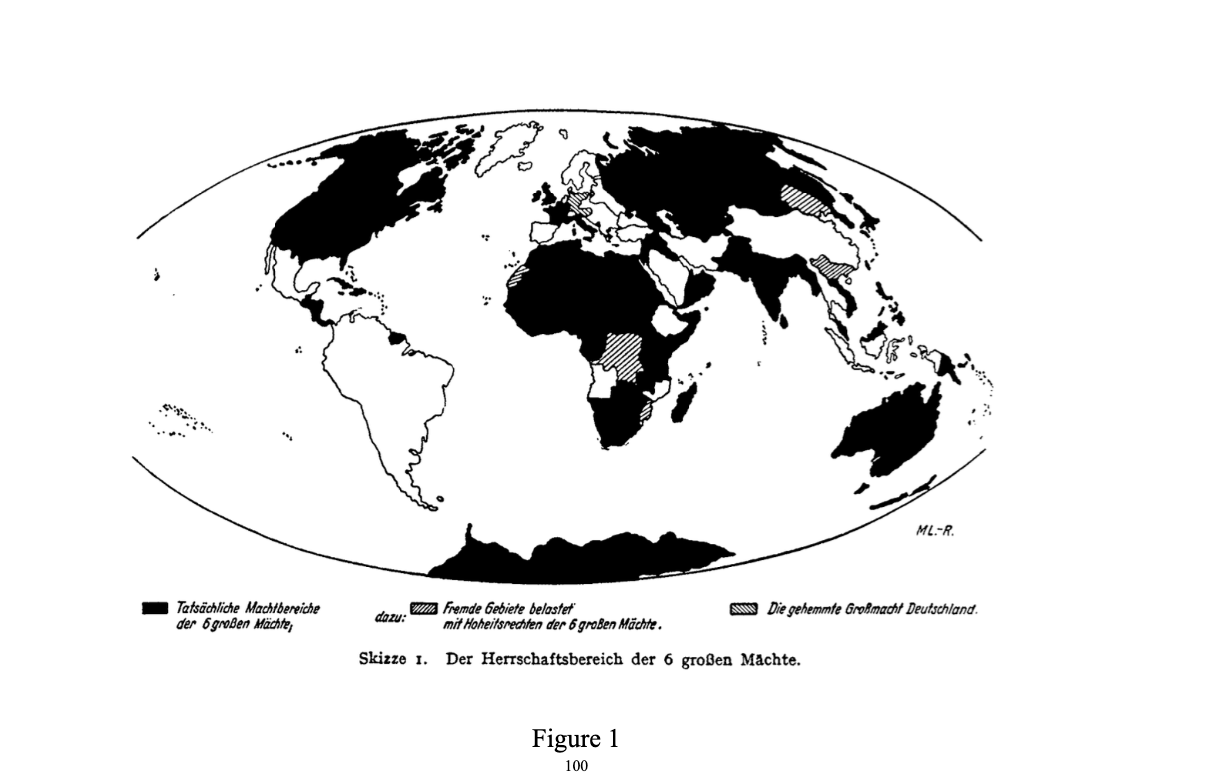

This analysis is cartographically depicted in Figure 1 [100].

The cartographic depiction of Figure 1 is titled “The Domains of the 6 Great Powers”. This includes all of the great powers analyzed except for Germany as it is considered to be inhibited. This cartographic depiction shows the “real” spheres of power of each of the great powers across the Globe as fully shaded areas. The shaded areas with lines pointing left to right present the “foreign areas burdened with Sovereign Rights” of the 6 great powers. Lastly, the shaded area with lines going from right to left presents the “inhibited great power of Germany”. Such an analysis leading to a geographic international law allowed Langhans-Ratzeburg to explain sources of conflict in certain regions as competing legal claims could be visualized [101]. Such visualizations had geopolitical significance as these spatial conflicts of possession intersected such that they represented characteristics of geopolitical properties [102]. These conflicts often arose in “geopolitical friction belts” [103]. Langhans-Ratzeburg also depicted how Germany was inhibited by the international legal order cartographically. This cartographic depiction can be seen in Figure 2 [104].

Figure 2 cartographically depicts how and in what ways Germany is inhibited from being a great power and which spaces it is being denied. The legend from the top to bottom reads as follows. The ban on “Anschluss” with Austria is represented as a bricked pattern and on the map is depicted as a high wall. Underneath this, in a criss-cross pattern, the fully demilitarized and dissolved regions are indicated. The restricted areas are represented. Small squares indicate past military strongholds of Germany. While the half moon represents destroyed military shelters [105]. Lastly, the line with dots above it depicts the internationalized rivers going through German territory. Through such depictions, potential “geopolitical friction belts'' can be identified as multiple great powers lay claim to these areas.

Geo Jurisprudence attempts to explain law and legal ordering as being geographically determined. In The Great Powers: Viewed Geo Jurisprudentially the geopolitical factors contributing to Germany’s inhibited position in the international legal order are explored and how international law has contributed to this. Through the cartographic depiction, it becomes clear that Langhans-Ratzeburg echoes contemporaries in claiming that the Treaty of Versailles inhibited Germany, moreover to overcome this the German state needs to “harmonize with the form of its living space” [106] and “must, following the cue of nature, assume a decentralized form” [107]. These arguments by contemporaries were received both positively and negatively. To further understand how the arguments previously discussed and geo jurisprudence itself were situated within the academic debate at the time several reviews of the general works of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg have also been considered.

An analysis of contemporary reviews of the works of Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg reveals that go jurisprudence was received generally positively as being a new analytical method. Walther Vogel, a geographer is generally supportive of the ideas that are put forth in the work of Langhans-Ratzeburg and especially praises that he uncovers the spheres of influence of the great powers [108].

In an earlier review of “Concepts and Tasks of Geographic Jurisprudence” Vogel is of the view that the move towards a "geo jurisprudence" is justified especially in combination with cartography [109]. Vogel has been critical however of geopolitical thought itself and its tendencies to not be analytically complete [110]. He gives the example of the discussion on rivers being decisive in what city becomes a state's capital, as argued by both Erich Obst and Langhans-Ratzeburg, however, Vogel points out that recent technological developments such as railroads are not being taken into account in these discussions [111].

Adolf Grabowsky, a geopolitician, is generally positive about the examples used by Langhans-Ratzeburg to elaborate his points [112]. Legal theoreticians are less enthusiastic about Geo Jurisprudence and emphasize that it is merely a method and not a new emerging field. For example, Leonhard Adam is firm in pointing out that geo jurisprudence is a method in which the use of cartography shows that it is an illustrative method [113]. Methodologically it therefore illustrates legal facts and does not lead to a new field of science, Adam warns of an overspecialization and splintering of the German geosciences [114].

Heinrich Richter, a lawyer, is the most critical of the work of Langhans-Ratzeburg and argues that norms cannot come from geographical facts [115]. Richter’s critique is based on an engagement with the thought of Hans Kelsen which is used to emphasize that geo jurisprudence only constitutes a method rather than producing new legal knowledge [116]. Agreeing with Richter, Koellreuter emphasizes that geo jurisprudence cannot be seen as a positivist legal theory due to not identifying norms directly [117]. Therefore, geo jurisprudence was generally regarded as a method to indicate relations between states and how geopolitical factors influence and determine these relations. As a method, it was according to contemporaries useful in uncovering the “real” spheres of influence of the great powers.

7. Conclusion

Conclusively, geo jurisprudence is an endeavor closely intertwined and influenced by the context in which it was produced which was the justification for the expansion of Germany. Geojurisprudential works highlighted how law, especially international law, constrained Germany and prevented its natural right to space. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg employed cartography to illustrate these arguments. The international legal order and international law from the perspective of geo jurisprudence are determined by geopolitical and geographic conditions. However, the claim of a geo deterministic development of law and actual international law is not touched upon in the works of Langhans-Ratzeburg. Rather as has been pointed out by David Murphy there is a lack of consistent explanatory power for geo determinism leading to the development of (inter)national law [118]. Writing closer to the ideas of geo jurisprudence Andrew Gyorgy claimed that geo jurisprudence is not law, not geography or politics [119].

Instead, Gyorgy points out that geo jurisprudence reflects National Socialist wishful thinking about space and power [120]. Situating the endeavor of geo jurisprudence of Langhans-Ratzeburg within the late-Weimar Republic it is evident that it has been influenced by contemporary spatial thinking. This endeavor therefore leads to Germany being portrayed as an inhibited power that reflects the contemporary stance regarding the German state’s position post World War 1.

The work of Langhans-Ratzeburg recognizes that there is a will within German discourse of expanding its territory, however, unlike the work of Carl Schmitt, it merely reflects the contemporary stance rather than being a major cog in the expansionist thought of the National Socialists. Overall, the work and endeavor of Langhans-Ratzeburg provide insight into how geopolitical thought was extended to other fields. Geo jurisprudence, as David Murphy aptly states, remains a chimera in attempting to draw law and its development from geography, especially international law.

Endnotes

Gordon, Peter Eli, and John P. McCormick. Weimar thought: A contested legacy,p.1.

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008,p.677.

Ashworth, Lucian M. “Mapping a New World: Geography and the Interwar Study of International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2013): 138–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12060,p.140.

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008,p.681

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008,p.682

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013.

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008, p.681.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996,p.26

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996. ,p27.

Ashworth, Lucian M. “Mapping a New World: Geography and the Interwar Study of International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2013): 138–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12060,p.140.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022,p.111

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022,p.101.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996,p.25.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022,p.104.

Bassin, Mark. “Imperialism and the Nation State in Friedrich Ratzel’s Political Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 11, no. 4 (1987): 473–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913258701100401,p.479

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022 ,p.113.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022 ,p.113.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022 ,p.114.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022 ,p.104.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022 ,p.114.

Translated into English : Journal of Geopolitics

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.32.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.32.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.33.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.34.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.34.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.34.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.34.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996, p.34.

“Katalog Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek.” DNB,. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://portal.dnb.de/opac/showFullRecord?currentResultId=%22manfred%22%2Band%2B%22langhans%22%26dea¤tPosition=1.

Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.111

Çapan, Zeynep Gülşah, and Filipe dos Reis. “Creating Colonisable Land: Cartography, ‘Blank Spaces’, and Imaginaries of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Germany.” Review of International Studies, 2023, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210523000050,p.16.

Çapan, Zeynep Gülşah, and Filipe dos Reis. “Creating Colonisable Land: Cartography, ‘Blank Spaces’, and Imaginaries of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Germany.” Review of International Studies, 2023, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210523000050,p.16.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.111

Pottage, Alain. “Holocene Jurisprudence.” Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 10, no. 2 (2019): 153–75. https://doi.org/10.4337/jhre.2019.02.01,p.168

Pottage, Alain. “Holocene Jurisprudence.” Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 10, no. 2 (2019): 153–75. https://doi.org/10.4337/jhre.2019.02.01,p.168

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.113

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.114

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.115-6

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.110

Chiantera-Stutte, Patricia. “Space, Großraum and Mitteleuropa in Some Debates of the Early Twentieth Century.” European Journal of Social Theory 11, no. 2 (2008): 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431007087473,p.198.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.117

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.112

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008.,p.682.

Minca, Claudio, and Rory Rowan. On Schmitt and space. London: Routledge, 2016,p.171

Minca, Claudio, and Rory Rowan. On Schmitt and space. London: Routledge, 2016,p.171

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.112

Minca, Claudio, and Rory Rowan. On Schmitt and space. London: Routledge, 2016,p.171

Hooker, William Alexander. “The State in the International Theory of Carl Schmitt: Meaning and Failure of an Ordering Principle.” Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science (University of London), 2008,p.127

Orford, Anne, Florian Hoffmann, and Robert Howse. “Schmitt, Schmitteanism and Contemporary International Legal Theory .” Essay. In The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780198701958.003.0012,p.215

Orford, Anne, Florian Hoffmann, and Robert Howse. “Schmitt, Schmitteanism and Contemporary International Legal Theory .” Essay. In The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780198701958.003.0012,p.215

Teschke, Benno Gerhard. “Fatal Attraction: A Critique of Carl Schmitt’s International Political and Legal Theory.” International Theory 3, no. 2 (2011): 179–227. https://doi.org/10.1017/s175297191100011x, p.181.

Legg, Stephen, and Alexander Vasudevan. “Introduction.” Essay. In Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, edited by Stephen Legg, 1–23. London: Routledge, 2011,p.6.

Buitendag, Nicolaas, and Nicolaas Buitendag. “Chapter 5 Case Study One : Law, Political Power and Borders.” Essay. In States of Exclusion: A Critical Systems Theory Reading of International Law, 123–48. Cape Town, South Africa: AOSIS, 2022, p.136.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.115

Buitendag, Nicolaas, and Nicolaas Buitendag. “Chapter 5 Case Study One : Law, Political Power and Borders.” Essay. In States of Exclusion: A Critical Systems Theory Reading of International Law, 123–48. Cape Town, South Africa: AOSIS, 2022,p.136.

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008, p.681.

Grabowsky, Adolf. “Das Problem Der Geopolitik.” Zeitschrift für Politik 22 (1933): 765–802. http://www.jstor.com/stable/43349632, p.787

Grabowsky, Adolf. “Das Problem Der Geopolitik.” Zeitschrift für Politik 22 (1933): 765–802. http://www.jstor.com/stable/43349632, p.789.

Grabowsky, Adolf. “Das Problem Der Geopolitik.” Zeitschrift für Politik 22 (1933): 765–802. http://www.jstor.com/stable/43349632,p.787.

Chloros, A. G. “What Is Natural Law?” The Modern Law Review 21, no. 6 (1958): 609–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1958.tb00498.x,. 609.

Latin for law of nations

Chloros, A. G. “What Is Natural Law?” The Modern Law Review 21, no. 6 (1958): 609–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1958.tb00498.x, p.609.

Wacks, Raymond. “Legal Positivism.” Essay. In Philosophy of Law : A Very Short Introduction, edited by Raymond Wacks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014,p.18

Spaak, Torben, Patricia Mindus, and Stephan Kirste. “The German Tradition of Legal Positivism.” Essay. In The Cambridge Companion to Legal Positivism, 105–32. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2021,p.114.

Kirste, Stephan. “Chapter 2 Natural Law in Germany in the 20th Century.” Essay. In A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence 12, edited by E. Pattaro and C. Roversi, Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1479-3_30, ,p.96

Kirste, Stephan. “Chapter 2 Natural Law in Germany in the 20th Century.” Essay. In A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence 12, edited by E. Pattaro and C. Roversi, Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1479-3_30, ,p.96

Kirste, Stephan. “Chapter 2 Natural Law in Germany in the 20th Century.” Essay. In A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence 12, edited by E. Pattaro and C. Roversi, Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1479-3_30, ,p.97

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.1

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.5

The german adjektive of “gehemmte” translates to both inhibited or stunted in English.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.15

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.21-24

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.14-56

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.58

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.114

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.117

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.127

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.124

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.148

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.148

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116.

This best translates to naturally equipped

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.227.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.227.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.214

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.213

Meyer, Henry Cord. “Mitteleuropa in German Political Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers36 (September 1946): 178–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2560933,p.179.

Meyer, Henry Cord. “Mitteleuropa in German Political Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers36 (September 1946): 178–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2560933,p.179.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.215

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.215

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.216

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022., p.113.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.217

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.,p.217

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.12

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.115

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.115

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.115

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931,p.235

Located for example near Küstring on the map

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.116

Vogel, W. Review of Die großen Mächte geojuristisch betrachtet by Manfred Langhans- Ratzeburg, . Geographische Zeitschrift, (1932): 233–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27813640.

Vogel, W. Review of Die großen Mächte geojuristisch betrachtet by Manfred Langhans- Ratzeburg, . Geographische Zeitschrift, (1932): 233–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27813640.

Vogel, W. Review of Die großen Mächte geojuristisch betrachtet by Manfred Langhans- Ratzeburg, . Geographische Zeitschrift, (1932): 233–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27813640.

Vogel, W. Review of Die großen Mächte geojuristisch betrachtet by Manfred Langhans- Ratzeburg, . Geographische Zeitschrift, (1932): 233–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27813640.

Graboswky, Adolf. Review of Die Grossen Mächte geojuristich betrachtet by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Geopolitik und Geojurisprudenz by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Die Staaten als Lebewesen.. Geopolitisches Skizzenbuch by Karl Springenschmid and Karl Haushofer, . Zeitschrift Für Politik, (1934): 292–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43349707 ,p.293-4

Adam, Leonhard. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz). (= Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, II. Heft.) by Manfred Langhans - Ratzeburg, . Archiv Für Rechts- Und Wirtschafsphilosophie 22, (January 1929): 334–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23684318.

Adam, Leonhard. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz). (= Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, II. Heft.) by Manfred Langhans - Ratzeburg, . Archiv Für Rechts- Und Wirtschafsphilosophie 22, (January 1929): 334–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23684318.

Richter, Heinrich. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz) Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. 2. Heft by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg, . Archiv Des Öffentlichen Rechts 54, (1928): 140–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44302024.

Richter, Heinrich. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz) Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. 2. Heft by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg, . Archiv Des Öffentlichen Rechts 54, (1928): 140–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44302024.

Koellreutter, Otto. Review of Die Grossen Mächte, geojuristich betrachtet by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Das Problem einer Geo-und EthnoJurisprudenz by Alexander Kästner and Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg, . Archiv Des Öffentlichen Rechts 60, (1932): 292–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44302278 ,p.293.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013,p.117

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008, p.686

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008, p.686

References:

Adam, Leonhard. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz). (= Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, II. Heft.) by Manfred Langhans - Ratzeburg, . Archiv Für Rechts- Und Wirtschafsphilosophie 22, (January 1929): 334–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23684318.

Ashworth, Lucian M. “Mapping a New World: Geography and the Interwar Study of International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2013): 138–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12060.

Bassin, Mark. “Imperialism and the Nation State in Friedrich Ratzel’s Political Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 11, no. 4 (1987): 473–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913258701100401.

Buitendag, Nicolaas, and Nicolaas Buitendag. “Chapter 5 Case Study One : Law, Political Power and Borders.” Essay. In States of Exclusion: A Critical Systems Theory Reading of International Law, 123–48. Cape Town, South Africa: AOSIS, 2022.

Chiantera-Stutte, Patricia. “Space, Großraum and Mitteleuropa in Some Debates of the Early Twentieth Century.” European Journal of Social Theory 11, no. 2 (2008): 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431007087473.

Chloros, A. G. “What Is Natural Law?” The Modern Law Review 21, no. 6 (1958): 609–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1958.tb00498.x.

Criekemans, David. “Geopolitical Schools of Thought/ A Concise Overview from 1890 till 2020, and Beyond.” Essay. In Geopolitics and International Relations: Grounding World Politics Anew, edited by David Criekemans, 97–155. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2022.

Graboswky, Adolf. Review of Die Grossen Mächte geojuristich betrachtet by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Geopolitik und Geojurisprudenz by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Die Staaten als Lebewesen.. Geopolitisches Skizzenbuch by Karl Springenschmid and Karl Haushofer, . Zeitschrift Für Politik, (1934): 292–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43349707.

Grabowsky, Adolf. “Das Problem Der Geopolitik.” Zeitschrift für Politik 22 (1933): 765–802. http://www.jstor.com/stable/43349632.

Gyorgy, Andrew. “The Application of German Geopolitics: Geo-Sciences.” American Political Science Review 37, no. 4 (1943): 677–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1950008.

Hooker, William Alexander. “The State in the International Theory of Carl Schmitt: Meaning and Failure of an Ordering Principle.” Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science (University of London), 2008.

“Katalog Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek.” DNB,. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://portal.dnb.de/opac/showFullRecord?currentResultId=%22manfred%22%2Band%2B%22langhans%22%26dea¤tPosition=1. Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg

Kirste, Stephan. “Chapter 2 Natural Law in Germany in the 20th Century.” Essay. In A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence 12, edited by E. Pattaro and C. Roversi, Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1479-3_30.

Koellreutter, Otto. Review of Die Grossen Mächte, geojuristich betrachtet by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg ; Das Problem einer Geo-und EthnoJurisprudenz by Alexander Kästner and Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg, . Archiv Des Öffentlichen Rechts 60, (1932): 292–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44302278.

Langhans-Ratzeburg, Manfred. Die Grossen Mächte : Geojuristisch Betrachtet. München & Berlin: R.Oldenbourg, 1931.

Legg, Stephen, and Alexander Vasudevan. “Introduction.” Essay. In Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, edited by Stephen Legg, 1–23. London: Routledge, 2011.

McCormick, John P., and Peter Eli Gordon. Weimar thought: A contested legacy. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Meyer, Henry Cord. “Mitteleuropa in German Political Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 36 (September 1946): 178–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2560933.

Minca, Claudio, and Rory Rowan. On Schmitt and space. London: Routledge, 2016.

Murphy, David T., and David T. Murphy. “Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg and Geojurisprudence.” Essay. In The Heroic Earth Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918-1933, 110–17. Ashland: The Kent State University Press, 2013.

Orford, Anne, Florian Hoffmann, and Robert Howse. “Schmitt, Schmitteanism and Contemporary International Legal Theory .” Essay. In The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780198701958.003.0012.

Pottage, Alain. “Holocene Jurisprudence.” Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 10, no. 2 (2019): 153–75. https://doi.org/10.4337/jhre.2019.02.01.

Richter, Heinrich. Review of Begriff und Aufgaben der geographischen Rechtswissenschaft (Geojurisprudenz) Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. 2. Heft by Manfred Langhans-Ratzeburg, . Archiv Des Öffentlichen Rechts 54, (1928): 140–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44302024.

Spaak, Torben, Patricia Mindus, and Stephan Kirste. “The German Tradition of Legal Positivism.” Essay. In The Cambridge Companion to Legal Positivism, 105–32. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Sprengel, Rainer. Kritik der geopolitik: Ein Deutscher Diskurs: 1914-1944. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., 1996.

Teschke, Benno Gerhard. “Fatal Attraction: A Critique of Carl Schmitt’s International Political and Legal Theory.” International Theory 3, no. 2 (2011): 179–227. https://doi.org/10.1017/s175297191100011x.

Vogel, W. Review of Die großen Mächte geojuristisch betrachtet by Manfred Langhans- Ratzeburg, . Geographische Zeitschrift, (1932): 233–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27813640.

Wacks, Raymond. “Legal Positivism.” Essay. In Philosophy of Law : A Very Short Introduction, edited by Raymond Wacks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Çapan, Zeynep Gülşah, and Filipe dos Reis. “Creating Colonisable Land: Cartography, ‘Blank Spaces’, and Imaginaries of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Germany.” Review of International Studies, 2023, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210523000050.